Your worldview is yours

Notes on assumptions, intentions, and perceptions

You can't assume that what's been blatantly obvious to you, and has always been blatantly obvious to you, is gonna be that way to somebody else.

I.

I grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, and moved to the U.S. in 2021 for university. Since then, I've had many "Welcome to America" moments that highlighted subtle cultural differences.

One of the most memorable involved making eye contact. Back home, looking someone straight in the eye, especially someone older, was considered disrespectful. So, I grew up conditioned to do the opposite: keep my eyes down and my gaze averted.

I carried that into my interactions in America because:

- From my point of view, maintaining eye contact was considered disrespectful.

- I wanted to be respectful.

The problem, of course, is that in America, not making eye contact can sometimes be viewed as a sign of disrespect. I don't remember exactly when I realized this, but it was months into conversations where what I thought was respectful was actually signaling the opposite.

II.

I work as a software engineer and use AI-assisted programming daily. These models are genuinely impressive, but if you've used them for anything remotely complex, you notice that they do not think for you. They take in the context you provide, map it to their internal model of the world, and return an output. You get out what you put in.

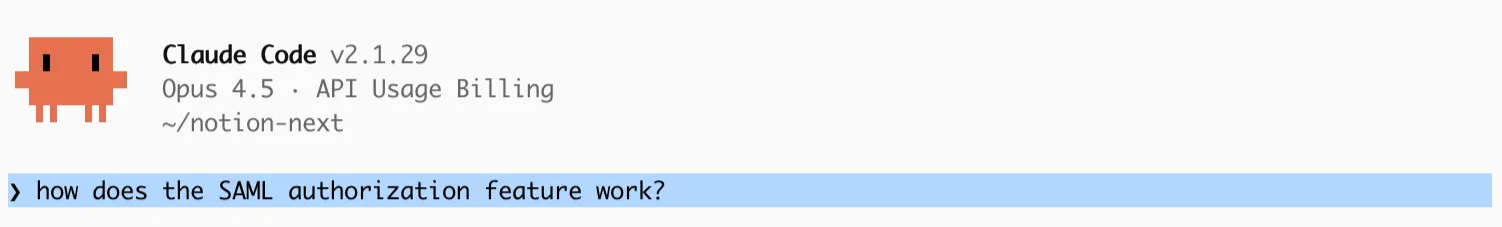

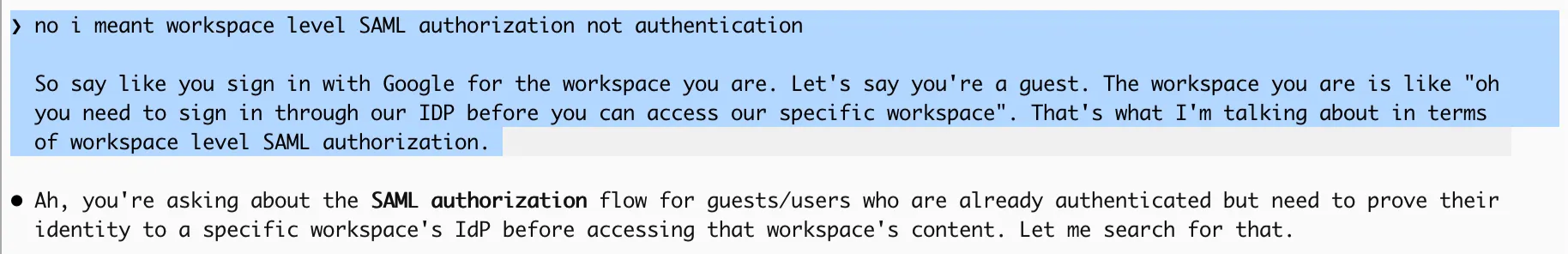

A few days ago, I wanted to refresh my understanding of how a particular feature worked, so I asked Claude to explain it.

This was my initial prompt:

It returned a long, detailed response about how SAML SSO authentication works. This was wrong. I wasn't asking about authentication; I was asking about workspace-level SAML authorization. The distinction is clear to engineers on my team who are deeply familiar with our systems, but fuzzy enough that Claude misinterpreted my intent.

I then tweaked the prompt:

This time it returned exactly what I needed.

I've seen AI skeptics who, after the first prompt failed, would have blamed the model and moved on. But the more useful mindset is meeting the model where it is; reorienting your perspective to match its internal worldview.

The underlying model didn't change. I adjusted my framing.

This piece captures this quite well:

When working with AI, the skill that matters most isn't prompt engineering. It's not about finding magic words or optimal templates. The real skill is the ability to put yourself in the agent's position—to model where it is in its thinking, understand why it went in a particular direction, and then adjust your framing to guide it somewhere else.

You have to hold your idea loosely enough to explain it multiple ways—and notice when the agent misunderstood, asking yourself why. Not "this is stupid, it didn't get it," but "what did I say that led it there, and how do I say it differently?"

— Thomas Osmonson

III.

One of the biggest pieces of feedback I received earlier in my career was that I needed to communicate my progress more visibly. I tended to be heads down, focused on doing the hard technical work. I collaborated well with the stakeholders directly involved, but I’d often treat broader updates as “admin work” that I could skip as long as the project was on track.

Part of it might be how I was raised: be humble, let your work speak for itself; so this kind of self-promotion didn’t come naturally. Another part is simpler: I genuinely found the technical challenges more fun than crafting polished Slack updates.

Either way, my thinking was that I’m solving real problems. I’m shipping. Fixing bugs quietly. The systems are better because of this work. Surely that’s enough; people would just know somehow.

But that’s exactly the trap. Why would anyone just know?

I was treating my worldview as a shared reality. From where I sat, the effort was obvious. I could see every late night, every edge case handled, every problem that crept up mid-project that wasn’t in the PRD. But my manager? My teammates? They’re managing their own deadlines and priorities. They don’t have access to my internal experience. They only see what I surface. “Let your work speak for itself” only works if your work is visible to the people who matter.

Now I view this visibility as an integral part of the job, rather than a nice-to-have. It helps other people make decisions, coordinate effectively, and trust what’s happening. When I put myself in my manager’s shoes, it clicks; there’s so much going on at every level of a company, and there’s genuinely no way to know what’s moving if people don’t surface their work.1

If you’re not proactive about communicating, you’re leaving your impact up to other people’s imagination. 2

IV.

There are dictionaries that live inside people. Entire languages no one else has learned. They are stitched together by childhood, by culture, by the endless reel of small moments that shape what we believe care should look like.

One person grows up believing love means asking a hundred questions a day. Another grows up believing love means leaving someone alone until they are ready to talk. Neither is wrong. Neither is right. But when those worlds touch, one feels interrogated, the other feels ignored. And suddenly a conversation about dinner becomes an argument about worth.

A lot of the friction I've experienced in my early adult relationships boils down to miscommunication: person A says or does something and assumes person B interprets it exactly as intended. Person B interprets it as something else entirely and assumes person A knew that all along. Suddenly you're arguing past each other.

Before my junior year of college, I'd been in the same long-term relationship and had mostly the same set of friends since primary/early secondary school. I was also surrounded daily by people who shared fairly similar outlooks on life, internal dictionaries, and overlapping context. That was my only reality, so I assumed it was the reality.

This meant I entered adulthood with fairly limited experience forming new core relationships, especially in a different country surrounded by people already set in their ways. I'd often treat someone I'd known for a few months the way I'd treat someone I'd known for a decade—a kind of premature closeness born from excitement, forgetting that it takes time to develop genuine trust and mutual understanding.

The problem is that when you've been around someone for years, you build up a ton of shared context, inside jokes, unspoken rules. A shared dictionary for what certain words and gestures mean. I had started to forget how much of that is built, not guaranteed on arrival.

So you might think: "I joke like this with people I love. It's how we've always been.” But then you meet someone new with a totally different internal world. They haven't built that dictionary with you yet. Through their lens, the same words that would have landed with laughs among your old friends might come across as hostile. And you're left wondering, with all your "good intentions" in hand, where things went wrong.

Your intentions can be completely noble. But they can't see your intentions. They can only see your actions, interpreted through their dictionary.

The thread through all of this is simple: the way you see the world is shaped by things unique to you—where you grew up, what you've experienced, who you've known. It’s so deeply yours that you can forget it isn’t shared; sometimes you might have to do a bit of translation to make sure your internal reality is legible to other people, especially the ones who matter to you.

To be clear, this is different from people-pleasing or editing yourself to be palatable to everyone. The goal here isn’t to lose yourself. It's about doing what you can to make sure your internal reality is understood with high fidelity. And I don't think that makes you less authentic. If anything, it's the opposite. There’s nothing inherently authentic about being misunderstood. If what you mean and what they hear diverge, your true, authentic self isn't actually reaching them.

If you can help it, why would you want to be misunderstood by people who matter to you?

So what now?

Every relationship is a collision. A meeting of two separate worlds that have no choice but to scrape against each other. It begins tender, with awe and curiosity. You see someone and you think, maybe I can fold my world into theirs, maybe theirs will make space for mine.

The biggest shift for me has been increased awareness; recognizing that I operate daily with tacit knowledge that isn't accessible to someone else. That alone changes how I show up. I try to factor in not just my worldview, but the other party's.

Beyond awareness, especially in personal relationships, there's the continual work of reconciling worldviews: really seeing someone, understanding the intricacies of their language, and developing the right tools to interact. Most of this work happens early, when trust is still being built, patterns still being understood, and maps still being constructed. But there's never a point of completion. Even the longest relationships have moments where gaps in the shared map lead to misunderstanding. The difference is that now there's a mutual commitment to working toward understanding, rather than falling into destructive conflict.

It took me some time to internalize this. Now, whenever I'm in a disagreement with someone I care about, where something I said or did clearly landed wrong, my first instinct isn't defensiveness. It's a kind of gentle curiosity; I peel back the layers to understand why my actions caused a certain reaction, then course-correct by updating our shared dictionary with what I learned. 3

Call it empathy, curiosity, or even efficiency4; the principle is essentially the same: before assuming someone understands your intentions, ask yourself what it looks like from their point of view.

Because regardless of what you're trying to say, do, or signal, if it doesn't land that way—if the other person's dictionary translates it differently—then what you meant is, in most cases, largely irrelevant.

Your worldview is uniquely, imperfectly, and irrevocably yours.5

"Distorted Worldview" - Mathew McGrane

Footnotes

-

There’s a conversation to be had about how this can incentivize optimizing for visibility over actual impact, and might overlook people quietly doing important work. But that’s a topic for another day. ↩

-

Tbh, I feel like this point applies to life more broadly. For the most part, it’s important to own your narrative. ↩

-

This also goes both ways. When I'm on the receiving end, i.e. someone does something that triggers a reaction in me, I try to pause and consider whether what they actually did was the issue, or whether past hurt, trauma, or insecurities might be causing me to project. Obviously, we're human, not robots; the goal isn't to be emotionless or to disregard your own boundaries for the sake of seeming emotionally in tune. It’s just to avoid assigning meaning that isn’t there. In a world where it's become fashionable to remove people from your life at the slightest inconvenience, a bit of tender curiosity and direct communication can go a long way, as opposed to cutting people off without extending any grace or holding space. ↩

-

For the pragmatists: spending less time and fewer words/tokens to convey your point is very high ROI. ↩

-

I wasn’t able to really explore this angle in this piece, but something else worth noting: just as you might assume others share your perspective by default, you can also assume that your internal narrative about yourself is fixed, objective reality. "I'd never be able to do that," "I'm not talented enough," "Oh, that's just the way I am." -- these feel like facts, but they're often just conclusions we locked in too early, maybe from a single bad experience or something someone once told us, and never revisited. Sometimes the most useful thing you can do is take bold action and test those definitions directly against reality: start before you feel ready, apply before you feel qualified, put real time into the thing you've already decided you're "just not good at.” This isn't the usual self-help "you can do whatever you want" advice, by the way. The main takeaway is realizing that your worldview is a lens, not necessarily universal truth, and you have the agency to update it. You’d be surprised by how malleable reality is. ↩